Shadow Empires: The Global Contest for Africa’s Strategic Minerals

Africa’s Critical Mineral Jackpot and the New Great Game

Africa stands at the center of a global power struggle not for ideology, territory, or traditional geopolitics but for the veins of the earth itself. Buried within its rich and often exploited soil are the critical minerals that power the modern world: cobalt, lithium, manganese, graphite, nickel, copper, and rare earth elements. These are not just commodities; they are strategic assets essential for the future of electric vehicles, energy storage systems, defense electronics, and green technologies that will define 21st-century civilization.

The Democratic Republic of Congo alone produces nearly 70% of the world’s cobalt, a critical component in batteries. Guinea holds vast reserves of bauxite, key to aluminum production. Zimbabwe and Mali are emerging lithium players. Meanwhile, South Africa and Gabon dominate in platinum, manganese, and chromium all vital for industrial resilience. Africa’s mineral bounty is indispensable, yet it exists amidst weak governance, porous borders, armed conflict, and underdeveloped infrastructure creating the perfect storm for external powers to intervene, manipulate, and exploit.

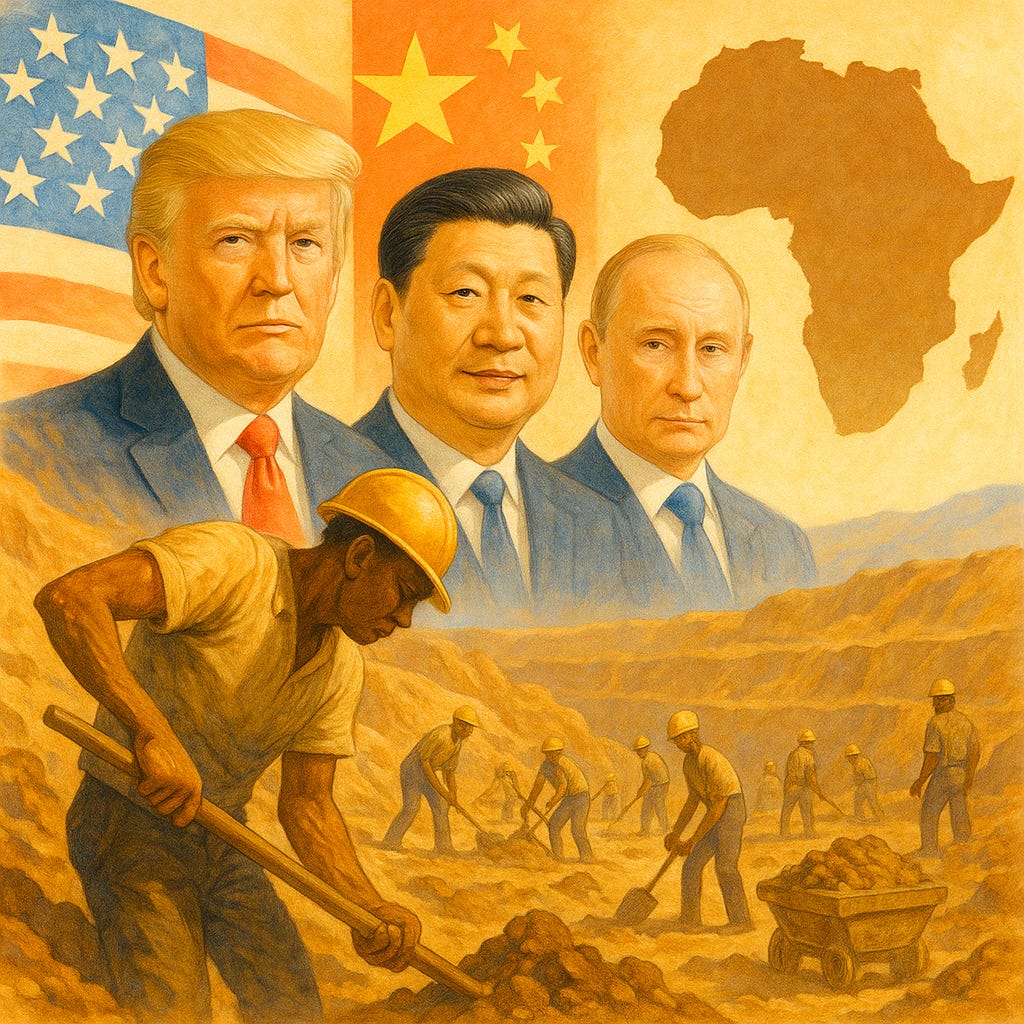

The new scramble for Africa is not like the colonial rush of the 19th century it's subtler, tech-driven, and hidden behind multinational deals, debt diplomacy, and private military networks. At the forefront of this strategic mineral war are three superpowers: the United States, China, and Russia. Each brings a different strategy economic entrenchment, covert operations, and militarized influence transforming mineral-rich zones into flashpoints of a multipolar competition that is as much about ideology and control as it is about profit.

China uses state-backed firms and infrastructure diplomacy under the Belt and Road Initiative to lock in mineral access through long-term concessions. The U.S., awakening to its strategic dependence, is moving rapidly to counter Chinese dominance with security alliances, intelligence operations, and supply chain partnerships. Russia, less conventional, leverages mercenary forces and hybrid warfare to seize influence over gold, uranium, and diamond mines in fragile states.

As these powers maneuver through a mix of diplomacy, sabotage, shadow finance, and military muscle, Africa becomes both a battlefield and a broker. The future of technological innovation, energy independence, and even military superiority hinges on control over these minerals. This article explores the full spectrum of this strategic battle through mines, mercenaries, intelligence footprints, and the opaque underworld of diamond and terror finance.

China’s Dominant Economic Footprint in Africa’s Mineral Sector

China’s engagement with Africa’s mineral sector is the most entrenched and strategically coherent among the three major powers. For over two decades, Beijing has methodically constructed a framework of economic influence that blends diplomacy, state finance, infrastructure development, and strategic investment into a seamless supply chain for critical minerals. Through its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China has positioned itself as the largest external player in Africa’s mining landscape extracting not only resources but also influence.

Central to this strategy are state-owned and state-backed Chinese mining giants such as China Molybdenum, Zijin Mining, Sinomine, and the battery manufacturing powerhouse CATL. These firms have acquired controlling stakes in cobalt and copper mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), lithium projects in Zimbabwe, and bauxite deposits in Guinea. In the DRC alone, Chinese companies control or co-own over 70% of the cobalt output often under opaque joint ventures with politically connected local elites. The $6 billion "infrastructure-for-minerals" deal between China and the DRC is a textbook example of how Beijing trades roads, hospitals, and schools for resource concessions.

China’s edge is further sharpened by its ability to deploy concessional loans and long-term repayment deals that trap African countries in a debt spiral. These financial instruments are often tied to infrastructure built by Chinese firms, which in turn facilitate the export of raw minerals back to China. For instance, Chinese-built railways in Zambia and Angola directly link mines to ports, reducing dependence on Western logistics or third-party intermediaries.

Moreover, China’s presence is deeply embedded within Africa’s digital and surveillance ecosystems. Smart city technologies, facial recognition systems, and data networks supplied by companies like Huawei and ZTE are installed in strategic mining towns and port cities. These systems collect vast troves of behavioral and logistical data, often routed back to Beijing. As a result, China’s influence extends beyond extraction; it shapes how Africa’s information and transport infrastructure functions.

China’s playbook also includes soft power investments, such as Confucius Institutes, scholarships, media partnerships, and military training programs. These efforts aim to engineer long-term alignment with African political and business elites, especially in mineral-rich countries. In doing so, China ensures not just current access to critical minerals, but future loyalty turning African resources into long-term pillars of its industrial and technological rise.

America’s Strategic Pivot and Covert Countermeasures

For much of the 2000s and 2010s, the United States ceded ground in Africa’s mineral sector to China, focusing instead on security, counterterrorism, and humanitarian missions. However, with the growing realization that clean energy technologies, semiconductors, and defense manufacturing all depend on critical minerals largely sourced from Africa and increasingly controlled by Beijing Washington is now recalibrating its Africa strategy. This new push involves both overt partnerships and covert operations designed to reassert American influence over the continent’s mineral supply chains.

The public face of the U.S. strategy is the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP), launched in coordination with allies like Canada, Australia, the EU, and Japan. Through the MSP and the Development Finance Corporation (DFC), the U.S. is financing lithium, rare earth, and cobalt projects in countries like Zambia, Namibia, and Madagascar. These investments are packaged with ESG compliance, anti-corruption provisions, and local beneficiation pledges to appeal to African governments and differentiate themselves from China’s extractive approach. The Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act further incentivized U.S. companies to onshore critical mineral sourcing through Africa-to-America corridors.

Yet behind this diplomatic charm offensive lies a more clandestine operation. The CIA, NSA, and other intelligence branches have increasingly shifted focus toward African mineral hubs, embedding analysts and field operatives in embassies across Kinshasa, Lusaka, and Maputo. These agents coordinate surveillance on Chinese and Russian activities, gather intelligence on infrastructure projects, and facilitate covert support to regimes that favor Western-aligned mineral deals. U.S. intelligence, working through partnerships with Israel’s Mossad and the UK’s MI6, also monitors trade-based money laundering and illicit mining logistics tied to rival powers.

Private military contractors (PMCs) and security firms such as Academi (formerly Blackwater), Triple Canopy, and DynCorp have re-emerged in the mineral-rich corridors of sub-Saharan Africa. Operating under training and advisory contracts with African governments, these PMCs often serve dual purposes: bolstering local security forces and safeguarding U.S.-linked mineral projects from insurgent threats or rival sabotage. In Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province, U.S.-aligned firms provide logistical support to military units protecting graphite and LNG installations, while subtly edging out Chinese commercial interests.

Through this layered approach diplomatic, financial, and covert the United States aims to decouple global supply chains from Chinese control and regain leverage in the global energy transition. Africa’s mineral fields have thus become more than commodities they are now geopolitical pivot points in America’s battle for industrial and strategic independence.

Russia’s Wagner Playbook and African Mineral Conquests

Russia’s strategic engagement in Africa is distinct from the models pursued by the U.S. and China. Instead of using economic influence or diplomatic partnerships, Russia operates in the shadows relying on private military companies (PMCs), covert arms deals, and direct arrangements with embattled regimes to carve out control over mineral-rich territories. At the heart of this approach, until recently, stood the Wagner Group Moscow’s most powerful non-state instrument of influence in Africa.

Wagner’s presence in Africa surged between 2017 and 2023, as it deployed thousands of fighters, trainers, and operatives to nations such as the Central African Republic (CAR), Sudan, Libya, Mali, and Mozambique. These countries, many of which are grappling with internal insurgencies or civil unrest, offered fertile ground for Wagner’s model: security for minerals. In exchange for protecting presidential palaces, suppressing rebellions, or training special forces, Wagner-linked entities secured access to gold mines in Sudan, diamond fields in CAR, and uranium prospects in Mali.

The deals were often struck in secret, facilitated by Russian diplomats and intelligence officers from the GRU (Russia’s military intelligence agency). Once on the ground, Wagner established extraction routes, logistical hubs, and air corridors that bypassed international oversight. These minerals were smuggled out through Russian-aligned states or ports, monetized through shell companies in Dubai, Syria, and Cyprus, and used to finance covert operations far beyond Africa.

Even after the death of Yevgeny Prigozhin in 2023 and the Kremlin’s formal absorption of Wagner into the Russian Ministry of Defense framework, this model has persisted. New PMCs like Redut, Convoy, and other GRU-linked outfits have inherited Wagner’s contracts, continuing the work of securing mineral access through a combination of armed force, disinformation campaigns, and elite co-optation. These groups now operate under tighter Kremlin control but with the same mission: expand Moscow’s strategic depth in Africa through raw resource capture.

What sets Russia apart is its willingness to operate in failed or semi-functional states. In many of these areas, Wagner or its successors act as parallel governments collecting taxes, providing security, and exporting resources without any formal accountability. This hybrid control gives Moscow asymmetric power, allowing it to finance its war economy, project global influence, and disrupt Western supply chains especially for gold, uranium, and diamonds that bypass formal markets. Africa has become a theatre of silent Russian conquest not through embassies or aid packages, but through guns, gold, and ghost soldiers embedded in the mineral veins of fractured states.

France’s Post-Colonial Shadow and Its Waning Mineral Empire

France, once the undisputed master of West and Central Africa through its colonial empire, still casts a long but fading shadow across the continent. For decades after independence, Paris maintained tight economic, political, and military ties with its former colonies under a system known informally as Françafrique—a network of elite relationships, defense pacts, and resource deals that ensured French access to Africa’s natural wealth. But in the current scramble for critical minerals, France finds itself increasingly outpaced by more aggressive and better-funded rivals like China, Russia, and now even the United States.

French influence in Africa has traditionally rested on three pillars: the CFA franc currency zone (which still binds 14 countries to monetary policies dictated in Paris), elite educational exchange programs that mold Francophone bureaucracies, and permanent military bases in strategic countries such as Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Djibouti, and Niger. Through these levers, France secured lucrative mining rights to uranium in Niger, gold in Mali, and bauxite in Guinea, often via French multinationals like Areva (now Orano), TotalEnergies, and Eramet.

However, the 2020s have marked a dramatic decline in French credibility across the Sahel and Francophone Africa. A wave of military coups in Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea, and Niger many of which ousted French-aligned civilian governments has been accompanied by popular uprisings against French presence. French flags are routinely burned in protest, and Russian flags now fly over many government buildings once closely tied to Paris. The ejection of French troops from Mali in 2022, followed by similar moves in Burkina Faso and Niger, reflects this geopolitical unraveling.

One of France’s biggest setbacks has been in Niger, where Orano’s uranium operations once supplied a third of France’s nuclear power needs. With the recent military regime threatening to nationalize or renegotiate contracts, France’s energy security is now in jeopardy. Meanwhile, Russia and China are actively courting these new leaders with promises of security, no-strings-attached aid, and alternative investment models.

Even in West African coastal nations like Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire traditionally stable French allies Chinese infrastructure projects and U.S. strategic investments are eroding Paris’ once-dominant role. French intelligence networks, though still operational, are now contested by more assertive players, and their ability to shape regional narratives is rapidly diminishing. France’s mineral empire in Africa is not yet extinct, but it is clearly in retreat. What remains is a legacy of control being eclipsed by a new multipolar contest one in which Paris must now compete on unfamiliar terms, without the unquestioned loyalty it once enjoyed.

India’s Strategic Foray into Africa’s Mineral Heartlands

India, historically a marginal player in Africa’s mineral landscape, is now stepping up its engagement in response to both geopolitical necessity and industrial demand. As the world’s fifth-largest economy and a rising technological and manufacturing hub, India is increasingly dependent on critical minerals like cobalt, lithium, rare earth elements, and copper resources that are limited domestically but found in abundance across Africa. Unlike the U.S., China, or Russia, India’s approach is characterized by soft diplomacy, capacity-building, and targeted commercial partnerships, but it is now evolving into a more assertive and strategic posture.

India’s recent interest in Africa’s mineral wealth is shaped by three driving factors. First, the country’s expanding electric vehicle, defense, and electronics industries require stable supplies of lithium, cobalt, and rare earths. Second, New Delhi seeks to reduce its dependence on China for processed minerals and rare earths, aiming to build alternative supply chains. Third, India views Africa as a geopolitical hedge in its broader rivalry with China, particularly across the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) and the Global South.

Indian companies, including Tata Steel, Vedanta, and JSW, have begun investing in copper and iron ore mining projects in Zambia, Namibia, and South Africa. State-backed entities like KABIL (Khanij Bidesh India Ltd.) a joint venture between three Indian public sector units are actively negotiating mineral access deals in countries like Madagascar, DRC, and Tanzania for lithium and cobalt exploration. In 2024, India signed a landmark critical minerals cooperation agreement with Namibia and another with the DRC, focusing on joint exploration, capacity-building, and setting up local processing units.

Diplomatically, India leverages its historical goodwill, shared anti-colonial legacy, and strong development partnerships through the Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation (ITEC) program. Over 30 African countries receive Indian aid and training programs, including scholarships for geology, mining, and engineering. Indian medical diplomacy, education exchanges, and digital connectivity initiatives further strengthen bilateral ties offering a softer, non-coercive alternative to Chinese infrastructure debt or Russian militarism.

India has also begun integrating its mineral strategy into broader security cooperation. Naval deployments, joint military exercises with coastal African nations, and its participation in anti-piracy patrols in the western Indian Ocean all reflect a growing security footprint aimed at protecting mineral shipping lanes and investment corridors.

Though India’s presence is still modest compared to China or even France, it is rapidly maturing into a serious strategic axis. By aligning commercial investments with diplomatic outreach and security cooperation, India is positioning itself as a credible, balanced alternative in Africa’s contested mineral order quietly embedding itself in the next chapter of global resource diplomacy.

Diamonds, Gold, and the Terror Finance Nexus

While cobalt, lithium, and rare earths grab global headlines for powering the clean energy future, another layer of Africa’s mineral economy operates beneath the surface both literally and figuratively. Gold and diamonds, long associated with warlordism and illicit finance, continue to play a central role in the continent’s underground economy. But their significance now extends beyond regional conflict. These high-value, low-volume commodities are increasingly linked to the financing of terrorism, covert operations by state actors, and shadow trade networks that facilitate hybrid warfare across Africa and beyond.

In West Africa, particularly in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, jihadist insurgencies have seized control of artisanal gold mining sites. These groups, including Al-Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), generate millions in revenue by taxing local miners, running smuggling routes, and laundering the gold through informal markets. Much of this illicit gold is funneled through countries like Togo and Ghana, then re-exported often mixed with legal shipments to markets in Dubai, Switzerland, and India. The untraceable nature of artisanal gold makes it an ideal vehicle for laundering funds and financing regional terrorism.

Diamonds follow a similar path of conflict and concealment. In the Central African Republic (CAR), despite international efforts like the Kimberley Process to halt the flow of conflict diamonds, armed groups aligned with or opposed to the government continue to control mines and levy taxes on diamond diggers. Wagner-linked companies have been directly implicated in managing and guarding these diamond mines, creating a flow of precious stones that bypass official export channels and are laundered through networks in Lebanon, Syria, and the UAE. These stones finance Russian influence operations, buy weapons, and sustain private war economies.

China’s involvement in this shadow economy is more indirect but no less strategic. Chinese traders, often operating through shell companies in Tanzania, Angola, and Guinea, dominate the downstream gemstone markets. These traders are sometimes linked to larger state-owned conglomerates that channel profits from the illicit diamond and gold trades into broader supply chain control. While Beijing denies any association with conflict trade, the scale of these networks and their alignment with China's broader resource goals cannot be ignored.

The U.S. has stepped up financial surveillance through agencies like the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) and has pressured allies like the UAE and Israel to tighten scrutiny on suspicious transactions. However, enforcement is patchy, and local corruption remains a major barrier. In many cases, the same political elites facilitating official mining deals are also complicit in illicit finance, making reform nearly impossible.

In the shadows of Africa’s gold and diamond markets lies a parallel world of clandestine funding supporting terrorism, state capture, and covert warfare, all while operating beneath the radar of global regulators.

Intelligence Operations and Proxy Warfare in Mineral Hotspots

Beneath the veneer of trade deals and development aid, a much darker layer of strategic competition plays out in Africa’s mineral-rich zones a battle waged by spies, cyber operatives, and proxy forces. As global powers fight for dominance over lithium, cobalt, rare earths, and other strategic minerals, intelligence agencies have turned African soil into a covert battlefield. The United States, China, and Russia each deploy highly specialized intelligence assets to monitor rivals, shape political outcomes, and control the flow of critical resources, often by igniting or manipulating internal conflicts.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, long a focal point of mineral extraction and violence, the CIA has quietly reactivated Cold War-era human intelligence networks to track Chinese movements, corrupt mining contracts, and regional militia affiliations. U.S. intelligence operatives stationed under diplomatic cover in Kinshasa and Lubumbashi work closely with local informants, NGOs, and satellite contractors to compile data on Chinese mining logistics and Russian mercenary infiltration. The goal is not just surveillance, but influence engineering power shifts in provincial governments, local military commands, and rebel factions to favor U.S.-backed supply chains.

China, for its part, maintains its own sophisticated intelligence infrastructure through the Ministry of State Security (MSS), often disguised as commercial or cultural staff within its embassies and BRI-linked firms. These agents collect HUMINT (human intelligence) and SIGINT (signals intelligence) across mining zones and ports, targeting American and French mining contractors, NGOs, and Western diplomatic traffic. Huawei and ZTE surveillance systems installed under the banner of “smart cities” or public safety have become a trojan horse for data extraction scanning everything from email servers to logistics manifestos.

Russia’s GRU and FSB intelligence services, working alongside Wagner’s remnants, have mastered the art of proxy warfare. In mineral regions like Mali and Sudan, Russian operatives cultivate local militias, provide them with arms and training, and use them to harass or sabotage Western mining operations. Disinformation is another potent tool. Pro-Kremlin Telegram channels, local radio stations, and cyber-influencers have been mobilized to spread narratives accusing Western companies of neocolonialism, environmental damage, or involvement in child labor often to destabilize public support for U.S. or French mining ventures.

Private intelligence firms also play an active role. Western outfits like Stratfor and London-based Hakluyt & Co conduct corporate espionage on behalf of multinational mining firms, while Russian and Chinese entities fund their own corporate security arms to influence bidding, labor negotiations, and regulatory decisions. These intelligence wars occur far from public view, but they shape who extracts, profits from, and ultimately controls Africa’s vast mineral wealth. In this invisible battlefield, every piece of ore is not just a commodity it’s a signal, a target, and a weapon in a global game of deception, infiltration, and strategic manipulation.

Military Bases, Strategic Ports, and Infrastructure Control

While mines may be the starting point for critical mineral extraction, control over infrastructure railways, highways, ports, and military bases is what determines who truly dominates the mineral value chain. In Africa, where logistics are often disrupted by weak institutions, poor road networks, and political instability, strategic infrastructure becomes a tool not just of economic convenience, but of geopolitical leverage. The United States, China, and Russia have all recognized this, turning infrastructure corridors and military installations into chokepoints of power projection.

China leads the pack in this domain, having invested in more than 40 deep-water ports across the continent under its Belt and Road Initiative. Many of these ports such as in Mombasa (Kenya), Dar es Salaam (Tanzania), and Lamu (Kenya) are strategically located near mineral-rich regions and trade routes. Although publicly marketed as commercial infrastructure, several of these ports are equipped with dual-use facilities, including hardened bunkers, extended runways, and command centers capable of serving naval and intelligence functions. China’s naval base in Djibouti, its first overseas military outpost, is a prime example. Just a few kilometers from the U.S. Camp Lemonnier, it serves as both a logistics hub for mineral exports and a staging ground for PLA Navy operations in the Indian Ocean.

The U.S., lacking a comparable infrastructure development model, focuses on military positioning. AFRICOM has quietly expanded its footprint across West, East, and Central Africa through a network of forward operating bases (FOBs), drone surveillance centers, and special forces outposts. While Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti remains its primary hub, other installations in Ghana, Niger (notably the massive drone base in Agadez), and Kenya offer staging points for rapid intervention and monitoring of mineral hotspots. These bases are officially for counterterrorism, but they double as geopolitical levers for securing nearby mineral supply chains.

Russia’s approach is more covert and improvised. Without the resources to fund large-scale infrastructure, Moscow relies on access negotiated through Wagner-linked deals. In the Central African Republic and Sudan, Russian military advisors have quietly taken over airstrips, repurposed mining roads, and used rebel-held zones as logistics corridors. These routes, though primitive, are well-guarded and serve the dual function of extracting resources and projecting presence.

Control over infrastructure thus serves multiple strategic purposes: enabling export of minerals, ensuring military projection, and reinforcing political alliances. As global powers jostle for influence, the contest over ports, bases, and rail lines becomes the backbone of the mineral war a silent campaign fought not with missiles, but with megaprojects, excavation trucks, and cargo manifests.

African Elites, Cronyism, and Strategic Dependency

In the new great game for Africa’s critical minerals, one of the most decisive factors is not military hardware or diplomatic finesse but the complicity, agency, and opportunism of African elites. Presidents, generals, mining ministers, and business magnates act as gatekeepers to resource access. Their decisions, often driven by patronage, personal gain, or political survival, shape the trajectories of foreign influence far more than public sentiment or policy debates. For the U.S., China, and Russia, courting these elites has become a central feature of mineral strategy sometimes through legal investment, other times through outright corruption and coercion.

China’s model has proven especially attractive to authoritarian regimes and ruling parties. The Chinese doctrine of non-interference, combined with long-term concessional loans and state-owned partnerships, offers elites a steady stream of funds without the burdens of Western scrutiny. In Zimbabwe, for instance, Chinese firms enjoy privileged access to lithium and chrome through partnerships backed by ZANU-PF insiders. In the DRC, key government officials reportedly hold silent stakes in Chinese joint ventures, enabling Beijing to bypass regulatory hurdles. Chinese infrastructure projects are often inflated in cost, creating surplus capital for kickbacks to ministers and provincial governors, while ensuring that loyalty is cemented not just diplomatically but financially.

The Russian approach is more overtly coercive. Wagner operatives have provided personal protection to leaders in CAR, Mali, and Sudan, reinforcing regimes in exchange for mineral concessions. In several cases, Wagner has played kingmaker arming rebel groups, influencing elections, or even facilitating assassinations to ensure compliant figures remain in power. Once installed, these leaders reward Russian firms with gold, diamond, and uranium mining rights under secretive terms, with little to no environmental or labor oversight. In effect, Russia purchases mineral access through the manufacture of dependency and fear.

The United States, while less willing to engage in direct bribery, uses other instruments such as security cooperation, elite training programs, and debt forgiveness as levers to win favor. However, its insistence on transparency, democratic norms, and ESG standards often clashes with entrenched patronage systems. Consequently, many African leaders view the U.S. as a cumbersome partner, more interested in lectures than leverage. In response, Washington has quietly shifted tactics, funding elite-friendly “civil society” groups and think tanks that influence regulatory frameworks in subtle ways to favor U.S.-linked companies.

This dynamic creates a paradox: the very leaders tasked with protecting national mineral sovereignty are often the ones auctioning it off. As long as mineral wealth is brokered through elite networks rather than national development strategies, Africa’s critical resources will remain susceptible to capture not by force, but by favors, friendships, and foreign patronage.

Africa as Battlefield, Broker, and Barometer of the New World Order

Africa today stands at the intersection of opportunity and exploitation, sovereignty and subjugation, abundance and vulnerability. Its vast endowment of critical minerals lithium, cobalt, graphite, manganese, rare earths, and more has transformed the continent into a geopolitical prize for the great powers of our time. What began as a resource race has now morphed into a hybrid conflict involving private armies, shadow financiers, intelligence agencies, and digital infrastructure each aiming to control the arteries of the 21st-century economy. In this new great game, the battlefield is not just underground, but across airwaves, supply chains, and governance systems.

The United States, China, and Russia have brought distinctly different models to the mineral war. China wields economic leverage through infrastructure, state-owned enterprises, and long-term concessional loans, embedding itself deeply into Africa’s mining and data ecosystems. Russia operates in the shadows militarizing mineral zones, deploying proxy militias, and smuggling gold and diamonds to fund its strategic expansion. The U.S. presents a rules-based vision, promoting ESG standards and formal partnerships, but increasingly relies on covert intelligence, private contractors, and proxy influence to catch up with its rivals.

At the core of this contest lies a simple but powerful truth: whoever controls Africa’s minerals controls the future. From electric cars and solar panels to hypersonic missiles and quantum computing, technological supremacy in the 21st century is rooted in the control of inputs buried beneath African soil. But this is not merely a resource issue it is a test of governance, sovereignty, and agency. Will Africa continue to be a pawn in global power struggles, or will it emerge as a broker with its own strategy?

To shift the balance, African nations must move beyond rent-seeking and cronyism. They must establish regional regulatory regimes, pool negotiating power through platforms like the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), and invest in local processing, labor rights, and environmental protections. Only then can the continent rise from resource vulnerability to strategic leverage.

The mineral war in Africa is not an isolated phenomenon—it is a barometer of the emerging world order. As the Cold War 2.0 between USA & China heats up amid rising multi-polarity, Africa’s mineral veins are fast becoming the arteries of a new multipolar system. How this war unfolds and how Africa navigates it will shape not only the future of clean energy and global trade but the very architecture of international power in the decades to come.

References

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). "Critical Minerals: Africa Holds Key to Sustainable Energy Future." UNCTAD, 2023. https://unctad.org

Amnesty International. “This is What We Die For: Human Rights Abuses in the DRC Mining Cobalt Supply Chain.” 2022.

The Sentry. “The Taking: Russia, Wagner and the Central African Republic’s Natural Resources.” 2022.

U.S. Department of State. “Minerals Security Partnership (MSP).” 2023. https://www.state.gov/minerals-security-partnership/

Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). “China’s Engagement in Africa: A Resource-Driven Strategy.” 2022.

International Crisis Group. “Getting a Grip on Central Sahel’s Gold Rush.” Africa Report N°282, 2020.

Global Witness. “Undermining Sanctions: How Diamonds Fuel Conflict in CAR.” 2021.

BBC Africa Eye. "How Russia is Expanding Its Influence in Africa." Documentary, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa

Reuters. "India Signs Mineral Agreements with Namibia and DRC for Cobalt and Lithium." 2024.

Le Monde Diplomatique. “Françafrique is Dead. Long Live Françafrique?” 2023.

African Development Bank (AfDB). “Africa’s Mineral Wealth and the Energy Transition.” 2023 Annual Report.

SIPRI (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute). “Private Military and Security Companies and their Role in African Conflicts.” SIPRI Yearbook, 2022.

Financial Times. “China’s Control of Cobalt and Lithium: Western Firms Face uphill Battle.” 2023.

U.S. Department of Defense. “AFRICOM Posture Statement.” Testimony to Congress, 2024.

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “Strategic Minerals and the New Cold War in Africa.” 2022.

Quartz Africa. “Inside India’s Mineral Diplomacy in Africa.” 2023. https://qz.com/africa

Bloomberg. “Russia Smuggling African Gold to Fund War Economy.” 2023.

The Diplomat. “India’s Expanding Maritime and Mineral Strategy in Africa.” 2024.

African Arguments. “Africa’s Leaders Are Switching Patrons—from Paris to Moscow and Beijing.” 2023.

Chatham House. “African Agency in Global Mineral Governance.” Briefing Paper, 2023.

Fascinating read! I’m Harrison, an ex fine dining industry line cook. My stack "The Secret Ingredient" adapts hit restaurant recipes (mostly NYC and L.A.) for easy home cooking.

check us out:

https://thesecretingredient.substack.com